About Primary Hyperoxaluria

What is Primary Hyperoxaluria?

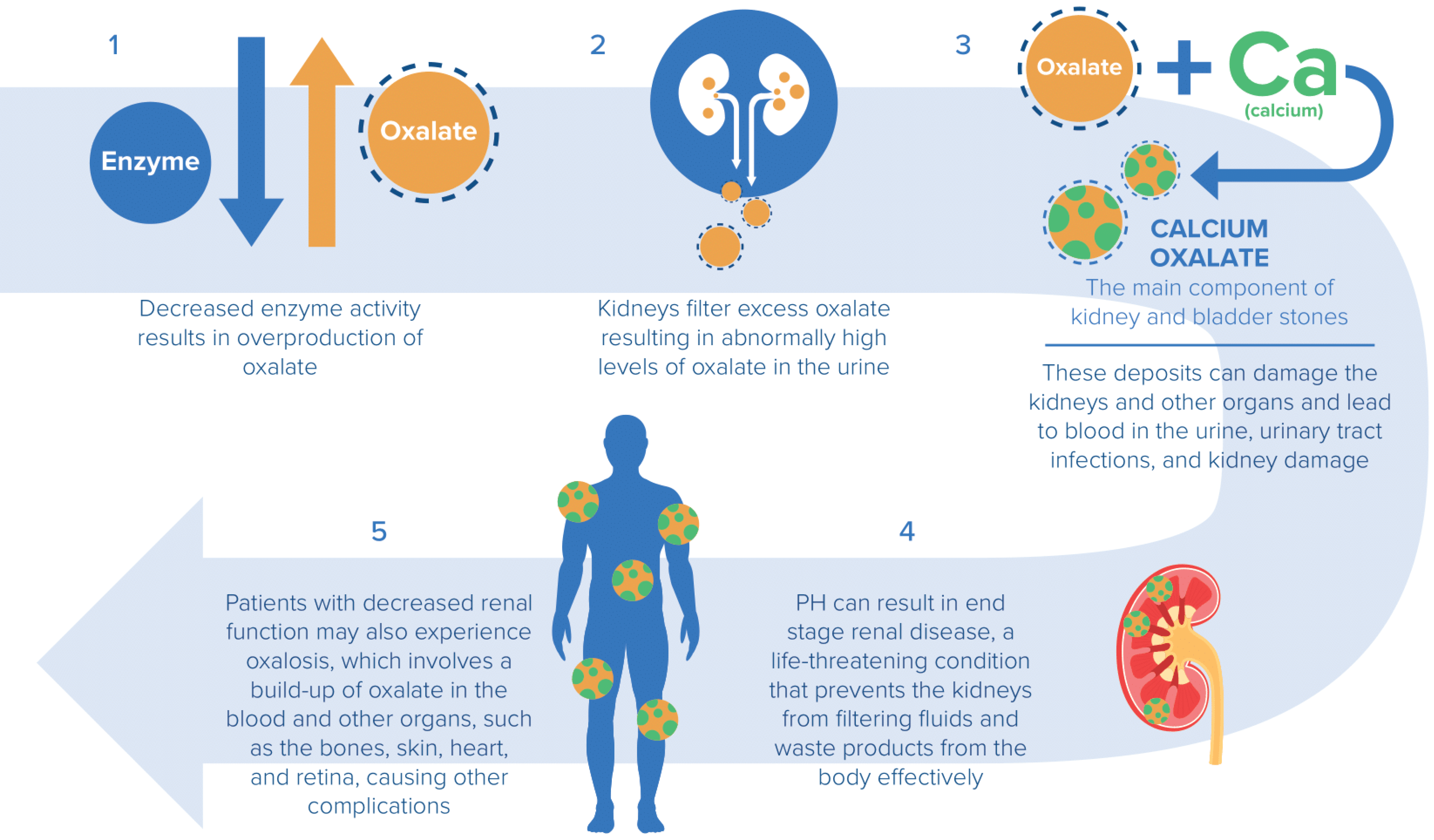

When too much oxalate accumulates in the kidneys, it binds with calcium to form calcium oxalate (CaOx) crystals. These CaOx crystals aggregate to form stones in the kidneys and urinary tract, and also distribute throughout the kidney tissue, causing nephrocalcinosis. As PH advances, progressive kidney damage may lead to end-stage renal disease, requiring regular dialysis and a dual liver-kidney transplant.

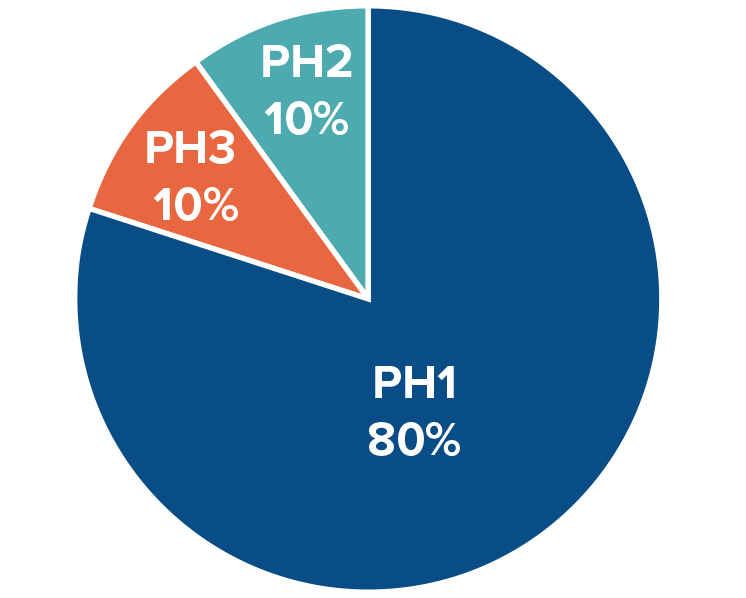

There are three known genetically defined subtypes of PH, each resulting from a mutation in one of three different genes.

| Subtype | Mutated Gene | Deficient Enzyme |

| PH1 | AGXT | alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase (AGT) |

| PH2 | GRHPR | glyoxylate reductase/hydroxypyruvate reductase (GR/HPR) |

| PH3 | HOGA1 | 4-hydroxy-2-oxoglutarate aldolase (HOGA) |

| Idiopathic PH (IPH) or No Mutation Detected (NMD) PH | Unknown | Unknown |

Signs and Symptoms

The warning signs of primary hyperoxaluria can include one or more of the symptoms listed below:

- Family history of kidney or bladder stones

- A single pediatric kidney stone

- Recurring kidney stones in adults

- Chronic kidney disease (CKD) with unknown etiology

- Nephrocalcinosis

- Systemic oxalosis

- End-stage renal disease (ESRD)

- Failure to thrive, ESRD, severe retinal abnormalities or vision loss in infants

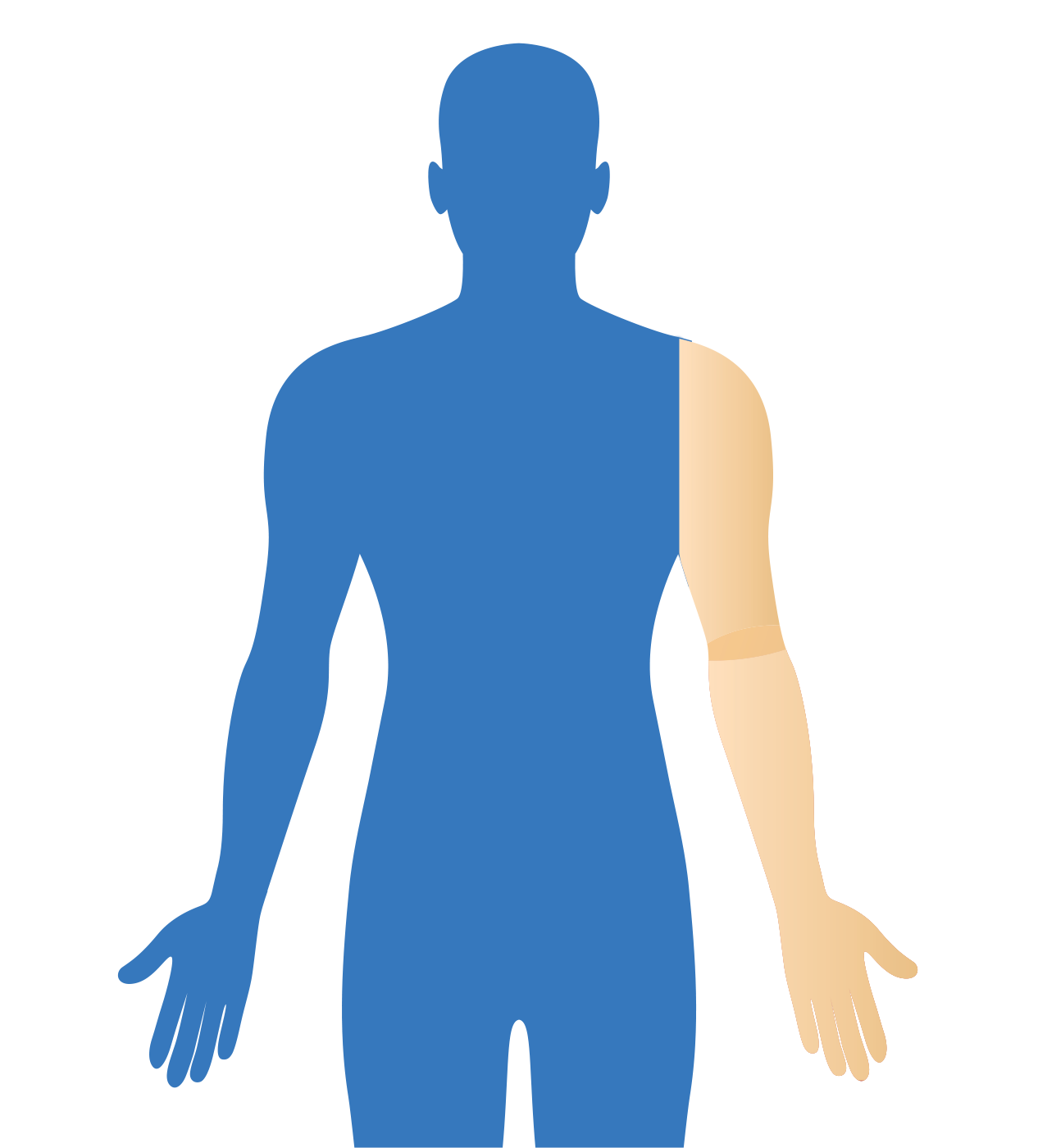

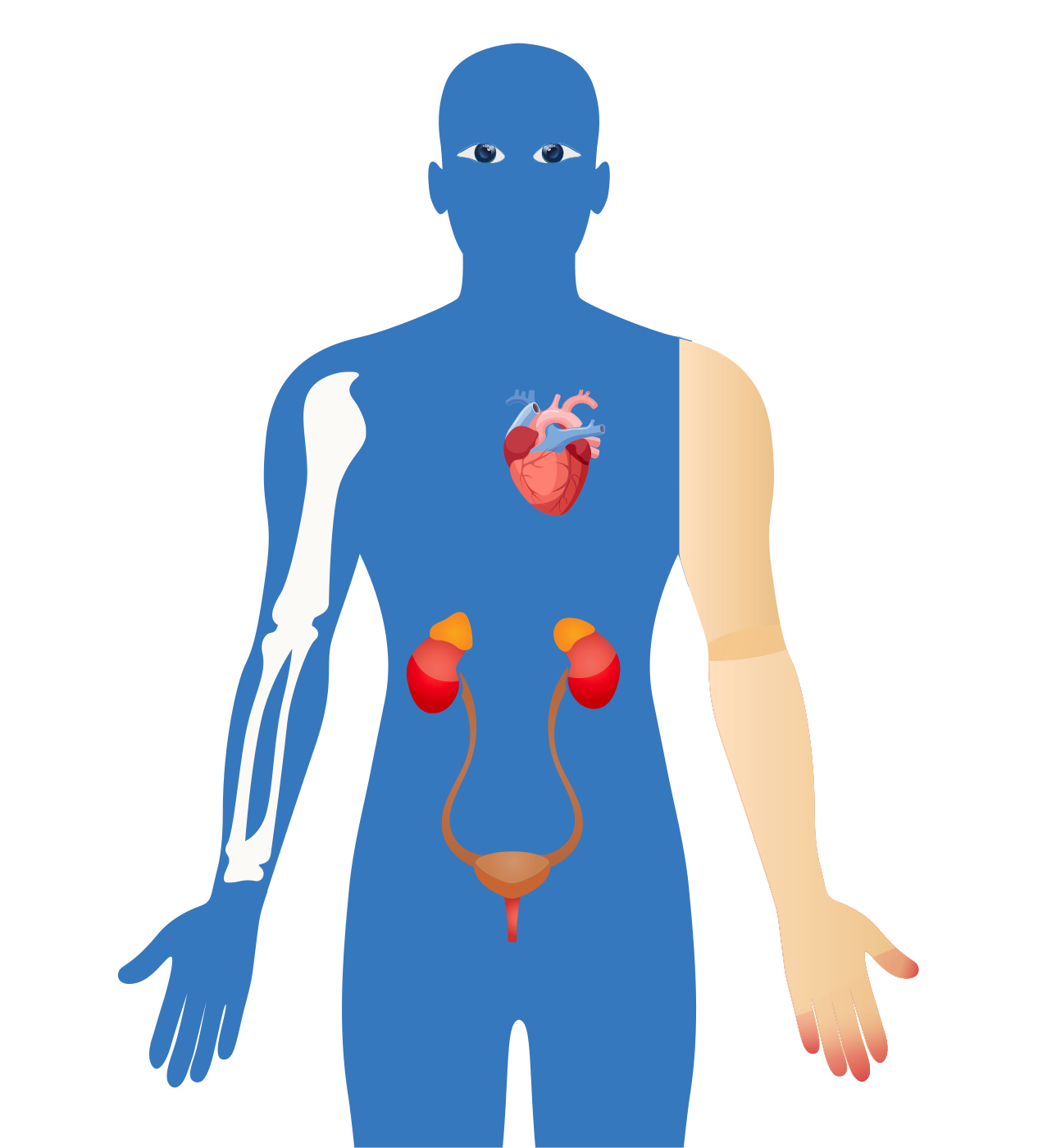

When kidneys start to fail, calcium oxalate can deposit in tissues throughout the body, causing a condition known as systemic oxalosis. Signs of systemic oxalosis include the following:

- Retinopathy and visual impairment

- Cardiomyopathy

- Cardiac conduction disturbances and heart block

- Stunted bone growth

- Recurrent low-trauma fractures

- Bone deformations with osteodystrophy

- Severe bone pain

- Anemia

- Skin nodules and ulcers

Progression of PH

Prevalence

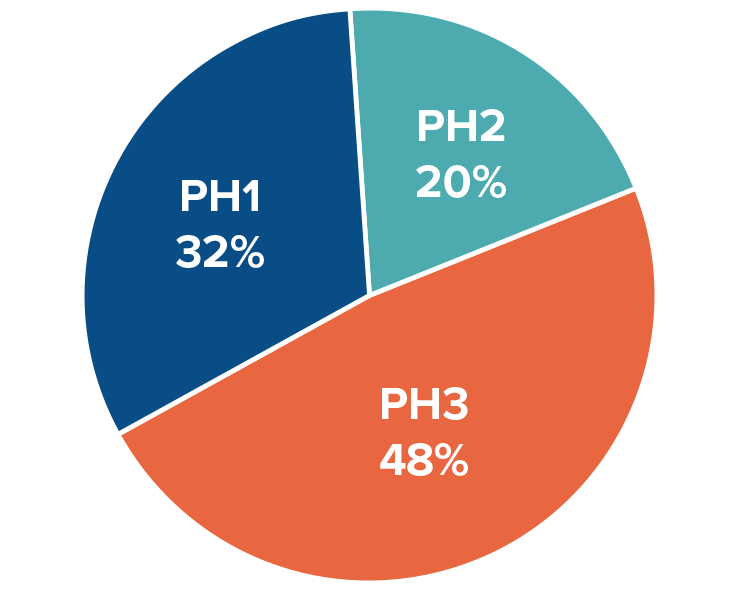

The distribution across the three known types of PH (PH1, PH2, and PH3) also differs between clinical studies and genetic studies. This data suggests that PH2 and PH3 are particularly underdiagnosed:

Unmet Medical Need

Researchers estimate that more than 80% of patients remain undiagnosed. Patients with severe PH may require regular dialysis and a dual liver-kidney transplant. Transplants are major surgical procedures; after transplant, patients must take immunosuppressant drugs for the rest of their lives. There is currently one approved therapy available that is limited to the treatment of patients with PH1.

Beck BB, et al. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21(2):162-172. Monico CG, et al. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(9):2289-2295.

Bhasin B, et al. World J Nephrol. 2015;4(2):235-244.

Birtel J, et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;206:184-191.

Cochat P, Rumsby G. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(7):649-658.

Danpure CJ, Rumsby G. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2004;6(1):1-16.

Dindo M, et al. Urolithiasis. 2019;47(1):67-78.

Edvardsson VO, et al. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28(10):1923-1942.

Garrelfs SF, et al. Kidney Int. 2019;96(6): 1389-1399.

Harambat J, et al. Kidney Int. 2010;77(5):443-449.

Hopp K, et al. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(10):2559-2570.

Johnson SA, et al. Pediatr Nephrol. 2002;17(8):597-601.

Mandrile G, et al. Kidney Int. 2014;86(6):1197-1204.

Neuberger JM, et al. Transplantation. 2017;101(4S)(suppl 2):S1‐S56.

OXLUMO [package insert]. Cambridge, MA: Alnylam Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2020.

Salido E, et al. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822(9):1453-146.

Sas DJ, et al. Urolithiasis. 2019;47(1):79-89.

Soliman NA, et al. Nephrol Ther. 2017;13(3):176-182. Frishberg Y, et al. Am J Nephrol. 2005;25(3):269-275.

U.S. Census Bureau population on a date: February 20, 2020. United States Census Bureau website, 2020.

van Woerden CS, et al. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18(2):273-279.

Williams EL, et al. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(8):3191-3195